Will we have time to recover from the Memorial Day floods before the next one hits?

Headed into San Marcos Sunday morning, May 24, evidence of the previous night’s storm was strewn all over the highway. Loose hay bales littered the shoulder of the road, and cars sat stuck in muddy ditches, abandoned by their owners. On the way to my family’s home near Highway 80, my stomach began to churn.

Just an hour earlier, pulled over at a gas station, I’d watched through a series of grainy Instagram snapshots as my aunt and uncle’s house filled up with rain water all the way to the second floor. Once the waters receded, my uncle documented what remained: My aunt’s beloved Cadillac was pinned to the ground by a neighbor’s truck, the piano on which I learned my first (and last) notes lay soggy and defeated on its side, and his Chevy Tahoe rested against a hole in the house.

Having spent the earlier part of the morning covering the annual convention of the American Coaster Enthusiasts at Schlitterbahn New Braunfels, I drove to their house still in shorts and river shoes, which I was grateful for as I waded through the front yard of my family’s home. Just hours after the Blanco swelled and burst all over Bogie Drive, panic began to set in. Up to her ankles in mud, my aunt and uncle’s adopted daughter Teri stopped and asked a family friend: “What are we going to do?”

Breaking Records, Bursting Dams

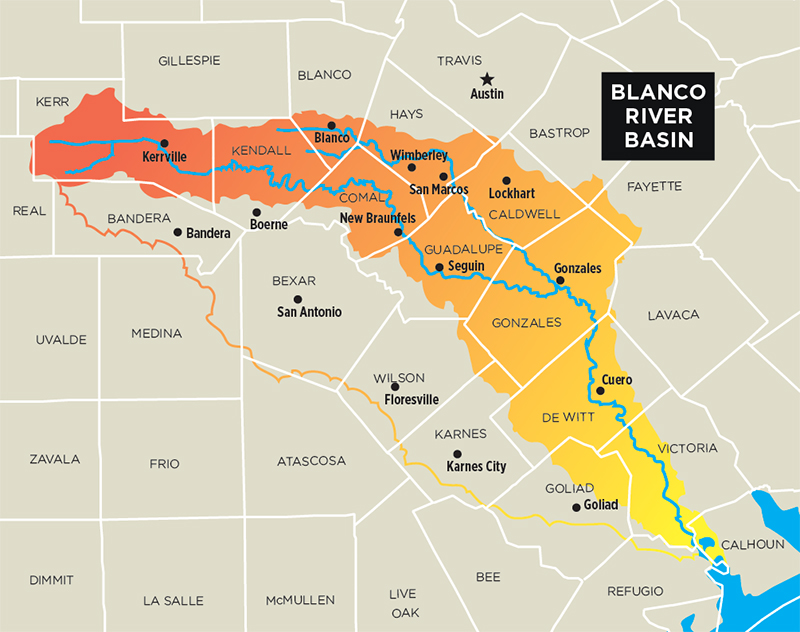

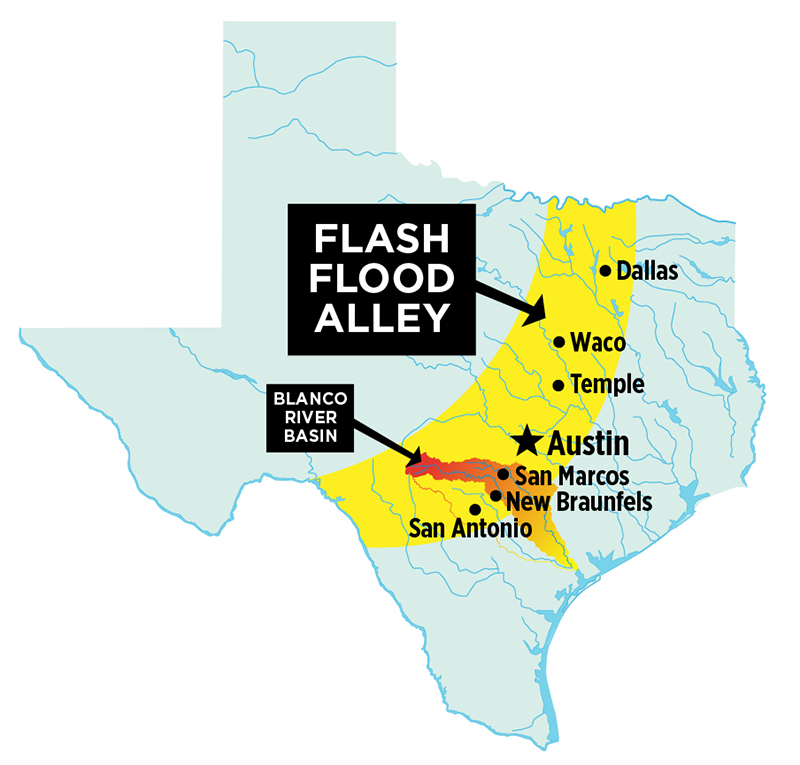

After a May with more than 20 consecutive days of rain – an “unprecedented,” record-breaking month, according to KXAN weathercaster Jim Spencer – rivers and streams in Central Texas were fit to burst by Memorial Day weekend. Then, over the following days, instability in the atmosphere coupled with moisture blowing in from the Gulf of Mexico created the perfect conditions for a massive flood event.

The KXAN weather team jolted into high alert. Saturday night Spencer and his colleagues went into continuous coverage starting at 9pm all the way until 7am on Sunday. In addition to the heavy rains pelting Blanco County, rotating thunderstorms had tornado warnings bouncing off the weather center walls. “It was really, really wild,” said Spencer, who’s been with KXAN for the last 25 years. “One of the craziest nights that we’ve worked because we started to see the historical nature of the flood that was happening.”

According to the National Weather Service, anywhere between 10 and 13 inches of rain fell over southern Blanco and northeast Kendall counties. At Wimberley, the Blanco River swelled from a comparatively modest five feet at 9pm Saturday to a staggering 41 feet by 1am Sunday. That wave of water devastated everything in its path, knocking out homes indiscriminately and savaging the cypress trees along its banks. Twelve people were killed. Spencer noted that the worst flood in the historical record dates back to the Twenties, when the water reached a height of 32 feet. After midnight on Saturday it became clear Central Texas was going to be marking a new record.

At his mother’s home in Wimberley, Marlin Forbes started watching the water sometime after 9pm. NWS warnings dinged on his cell phone. His sister, Nanette, called to make sure he was watching the weather. In turn, he asked for an idea of how far the river might reach; Nanette had been through several floods in the house. The city of Wimberley began calling to suggest homeowners seek higher ground.

“Even the news had no clue,” she said. “They were saying 23 feet, moderate flooding. I told my brother, I said, ‘You’d better watch the news.’ But they didn’t even know.”

“I remember, on the air, saying, ‘I can’t even believe what we’re seeing here,'” Spencer recalled. “‘You folks that live along the Blanco River: If you have ever flooded before, you will definitely flood this time. And places that haven’t flooded before are going to flood, because this is like nothing we’ve ever seen before.'”

Leading into the holiday weekend, the city of San Antonio assembled a group of representatives from the city’s fire department, the NWS, and the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office to warn the public about the potential for disaster. Among them was Joe Arellano, meteorologist in charge at the Austin/San Antonio National Weather Service forecast office, who expressed concern that the region’s soil couldn’t sustain the impending downpour.

“As the heavy rains fall, they hit the ground and, because the soil is very shallow, it runs very quickly into these low-water crossings, streams, and into the rivers,” Arellano said. “You might call it the perfect storm. It occurred under worst-case conditions. A lot of rainfall prior, very saturated grounds, and all this rainfall falling on the headwaters of the Blanco River. Everything just kind of came together to create the worst-case scenario.”

For its part, the NWS upgraded its previous flash flood warning into a full-on emergency by Sunday morning, warning homes and businesses were in danger. That designation is used, in part, to combat the fatigue residents experience when they live so close to the water. Weather alerts aren’t precise enough to pinpoint small areas, so residents begin to ignore warnings they think don’t apply to them. “When we have a big, prolonged event like we had in May, you see warning after warning being issued,” Arellano explained. “This is why we upgraded it to a flash-flood emergency. We don’t issue those on just a regular flood warning.

“[When] this is something very significant that will be causing significant damage, possibly deaths, is when we issue the flash-flood emergency message,” he continued. “Hopefully this is going to let people know this is not an ordinary case, but with warnings going out for hours, people get a little bit fatigued and start to tune it out. When they don’t see it happen in their location, this is when they kind of let their guard down perhaps. So they don’t see it coming until it actually hits.”

Worst-Case Scenario

An NWS report from 1972 highlights just how long the region – and the country at large – has been unprepared for a disaster of this magnitude. Forty-three years ago flash floods swept through the Texas Hill Country, ravaging New Braunfels and the surrounding areas to the tune of $20 million – over $100 million in today’s money. Eighteen people were killed. Then, as in May, warning systems, by radio or TV news, went in many cases unheard. From the report: “Only a few home owners took out [flood insurance] policies; as one citizen said, ‘We have not had a flood since 1952 and with the new dam, I did not think it would flood again.'”

In 1972 Hurricane Agnes pummeled the East Coast, costing the U.S. “more in disaster assistance than any previous disaster,” according to FEMA. Congress had passed the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 just four years earlier, and less than a million households had coverage.

Carol Haddock, a civil engineer at the Planning and Development Services Division of the city of Houston, has vivid memories of that ’72 flood as a kid. Years later, attitudes about infrastructure haven’t changed all that much. This year’s Blanco flood massacred the dams in its path, too.

“Then we came in and built levees and protections and dikes and all of those things, and we made man-made infrastructure and tried to build our way out of flooding, and those work until they’re overtopped,” Haddock said. “There’s always the possibility that there’s going to be a storm that’s worse than what we design for.”

Haddock explained that local governments lack both incentive and resources to stop recurring floods, partly because the best solution might be relocating entire households. Unlike Houston, which experiences “bathtub” flooding (in flat terrain, floods flatten out and become more predictable), where homes can be raised on stilts to protect from future damage, Central Texas experiences flash flooding, which makes that impractical. When rains fall over the Hill Country, water runs downhill and collects in low-water crossings, streams, and rivers. Anything in its path is fair game.

“Our response in recovery is usually: How do we get you back to the way you were as fast as we can?” Haddock said. “And when one of these disasters happens, we need to pause and we need to stop and we need to say: How do we help you recover as fast as you can, but should we recover you back to exactly where and how you were? And we haven’t been asking that question.”

A Recurring Problem

The Halloween flood at Onion Creek two years ago was the third since that neighborhood was built in the Seventies. There’s a city buyout process, but it has been painstakingly slow, and not just because of economics. Even if every bureaucratic hurdle is cleared the first time, there are endless delays in allocating funds, contracting, and appraising homes.

Property owners affected by the Halloween flood of 2013 finally gained another inch toward buyouts in March, when City Council approved another 240 homes (see “Council Defers on Decker, Approves Onion Creek Buyout,” March 10). Even though the volatility of the area isn’t in doubt, as the Chroniclereported, “some Council members worried that the action would set a precedent for the city to purchase all homes in 100-year flood plains (city staff estimates about 5,700 such homes).” Haddock noted that while local governments frequently pay up front for disaster relief efforts, they’re often reimbursed through federal disaster declarations, like the one signed by President Obama on May 30.

“So it’s not the local budgets that are being hit by that, so the long-term incentive for local entities is to maximize that tax base, and allow the federal government to come in during disasters,” Haddock said.

Between the last major flood in 2001 and Halloween 2013, the city bought out 300 properties. It still wasn’t enough. The Austin American-Statesman reported last year that due to Congress’ tight purse strings “more than 160 homeowners in Austin’s highest-risk flood zone … who could have received buyouts and relocated years before,” saw their homes flood.

Both the city of Austin and Hays County have commissioned after-action reports on how effective warning procedures were in the lead-up to Memorial Day. It’s standard procedure, and though we may learn more effective ways of warning people about danger, it won’t stop the next flood, nor will it speed up the buyout process.

“So [homeowners will] repair it and then 10 years in it’ll flood again, and about the third time they’re like, ‘You know what? I don’t want to recover like this again,'” Haddock said. “‘I want to do something different.’ Whereas the types of flood that you had in Wimberley, it’s a very different kind of recovery. I would have a hard time sleeping in a cabin with the rain, knowing that the river can come up that quick. I think a lot of people will.”

Troubled Water

Marlin and Nanette Forbes’ 89-year-old mother, Nona Forbes, still struggles with the decision to rebuild. Currently living in a small apartment in Kyle, she has days when she wants to restore her old home on the Blanco. Other days she’s unsure.

“There’s that underlying fear that it could happen again,” Nanette said.

“I think when she saw how fast it happened, [she realized] she could have very easily been caught in the house,” added Marlin. “I think that frankly scares the hell out of her. That she could be in another situation where she could drown.”

After securing his family with neighbors on high ground, Marlin began to keep tabs on the river’s progress. He could only watch as the river rose up and engulfed the house. The family would later reassemble and find the house devastated, with water reaching three-and-a-half feet past the second floor.

“And then, to be honest with you, I got sick,” Marlin said. “It made me ill. And when the water got to the roofline of the house, I left.”

Down the block from the Forbes’, the home where Corpus Christi resident Jonathan McComb and his family were spending Memorial Day was completely washed away. According to the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, McComb was “treated for a collapsed lung, broken rib and sternum.” His wife, Laura, and son were later found dead. His daughter was never found, but is presumed dead.

Those who managed to escape having lost just possessions face more than the complicated issue of rebuilding. “I was in shock,” Marlin said. “A friend of mine is a psychologist, and I called her one day and said, ‘I’ve got post-traumatic stress. I’m in this hole, and I can’t get out of it.'”

UT psychology professor Mark Powers said nearly 100% of people who experience a trauma like this will experience post-traumatic stress disorder-like symptoms. For most people, he noted, symptoms will ease within 12 months. “So, in other words, re-experiencing symptoms like nightmares and flashbacks; avoidance symptoms like not watching the weather, or not going to places that remind them of the trauma; and then hypervigilance, or feeling on edge and jumpy all the time,” Powers said. “Most people have some of those after the trauma – almost all.”

The treatment for this kind of trauma, called prolonged exposure (PE) therapy, was developed by University of Pennsylvania professor Edna Foa. In about 12 sessions, victims rehash their experience until they are able, as Powers puts it, “to file away that memory so it stops coming back to bother them.”

Of the people who go through a disaster like this, most will find their symptoms lessen over time. Still “a sizable percentage of these individuals (15-25%) will continue to report symptoms” and can be diagnosed with PTSD, Powers wrote in an email. Though PE is 85% effective, “most people aren’t aware of that treatment, and most people do not get that treatment. Only about 7% of people end up getting that treatment.”

“It took a while to work through it,” said Marlin, who considers himself lucky to have received treatment. “I would say there’s still a lot of it that I haven’t worked through. [PTSD is] real, and it’s really, really tough.”

Long-Term Forecast

Marlin Forbes says that cracking cypress trees pop like gunshots. Mid-afternoon May 24, I walked down to the bank of the Blanco, and studied the great exposed roots towering over me. After the storm, the city of Wimberley released a pamphlet telling residents to leave what was possible; the dead trunks will host the next generations of cypress growing on the river. A few scattered branches are already sprouting.

Weeks after the initial deluge, my family, like so many others, is still in recovery mode. Aided by family, friends, and volunteers, my aunt and uncle gutted their house and began working doggedly on a rebuild. Volunteers from the Billy Graham Ministries of Ohio secured and installed 90 sheets of drywall.

Wimberley’s river gauge was destroyed sometime around 1am on Sunday, measuring 40 feet, but the U.S. Geological Survey estimates the water eventually rose to near 45. Forbes and Haddock both used the word “tsunami” to describe the towering wall of water. Repairs to that gauge aren’t going to be enough.

“If we’d had a gauge upstream from Wimberley, we would’ve seen the crest coming, how big it was, and probably [have been] able to forecast the crest at Wimberley with much better accuracy than we were able to,” Arellano said.

The city of Wimberley and Hays County are working on installing new gauges, and it couldn’t come at a better time. Following two months of torrential downpours, July in Central Texas was bone-dry. That isn’t expected to last long. Both Spencer and Arellano predict an especially wet autumn and winter because of the possibility of a visit from a record-breaking El Niño.

With more rains likely headed for Central Texas, decisions on land-use only become more important. Residents in San Marcos have expressed concerns that an apartment development called the Woods of San Marcos might have played a role in diverting the Blanco runoff and worsened the damage. The city of San Marcos, whose recently adopted comprehensive plan is titled “A River Runs Through Us,” confirmed that they’ve commissioned a study into the matter.

The American Society of Civil Engineers released an aggressive report last year on the state of our preparedness for disaster. They warn that the U.S. hasn’t learned the lessons laid out after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and programs like the National Flood Vulnerability Assessment, “nearly nine years following Katrina, … have not been completed or in some cases even begun.” They chide both the president and Congress for having “no common vision of how the nation should organize and coordinate to reduce its flood risk,” and point out we don’t have a fully “sound” analysis of flood risk. And politicians are, well, playing politics with infrastructure money.

“You’ve got to have the good predictions about where the problem areas are,” Haddock said. “And then you’ve got to have the regulations, and in some cases, the political will to say, ‘We shouldn’t be in these areas.'”